Piazza San Pier MaggiorePiazza San Pier Maggiore is a city “hinge”. The main street joining it to the centre – Borgo San Piero – runs straight into commercial hub of the Renaissance city at Mercato Vecchio. It’s a tendril sprung out from the core of the city in the early Middle Ages as the Roman walls became too small to accommodate the population. In fact, it is the extension of the main east-west artery of the Roman town of Florentia – the decumanus – and heads out, beyond the piazza, out of the city east, towards Arezzo. The piazza formed around the church and the city gate on the second (late twelfth century) set of walls just beyond. From there, outside the walls, streets radiate in three different locations, the channeled movement directing to different districts (including Sant’Ambrogio to the East and Monteloro to the North). As an important node Piazza San Pier Maggiore attracted powerful residents – like the Donati and Albizzi – as well as being the stage for various urban rituals. It was also a thriving commercial area, adjacent to the gates, where taverns and other amenities were provided for travelers.

The Piazza San Piero Maggiore is quite an unusual space – it has none of the regular forms or columnated order of the “ideal piazza”, and yet it was a key space in the city, both for its association to a number of leading city families and for the presence there of the most important and oldest Benedictine convent in Florence, dating from at least 1066. The space had acquired its form by the end of the twelth century, as the road leading from the city towards Arezzo (Borgo San Piero) widened out in front of the church of San Piero Maggiore, and before the city’s eastern gate, just beyond – and also now-demolished. All that remains of the church today is a seventeenth-century three bay portico originally built to buttress the ancient church. Facing it, across the square is a fourteenth-century palace of the Corbizzi, with distinctive stepped overhangs that allowed the building to be larger on its upper floors. Flanking the palace to the left is a medieval tower, alegedly belonging to Corso Donati, whose constant fighting with neighbouring Cerchi family won him a place in Dante’s Divine Comedy as one of the instigators of the city’s thirteenth-century factional split between black and white guelphs. As Giovanni says, during the Renaissance the Albizzi had become the key family on the square and the principal ritual played out there was the remarkable “marriage” between the Abbess and each new Bishop of Florence. This event symbolically sealed a relationship between equals between male bishop and female monastic orders; as Sharon Strocchia has argued, the changing nature of that relationship by the later sixteenth century “recast the abbess as a dutiful daughter subject to paternal commands, rather than as a subordinate but still powerful wife.” The decline of the fortunes of the convent of San Piero (and its associated rituals) can be seen by the eventual erasure of the church itself, demolished as unsafe in the eighteenth century. Fabrizio Nevola To cite this essay, we suggest: Fabrizio Nevola, ‘A slice of piazza’ published online 2013, in ‘Hidden Florence’, The University of Exeter, https://hiddenflorence.org/stories/7-a-slice-of-piazza-piazza-san-pier-maggiore/ |

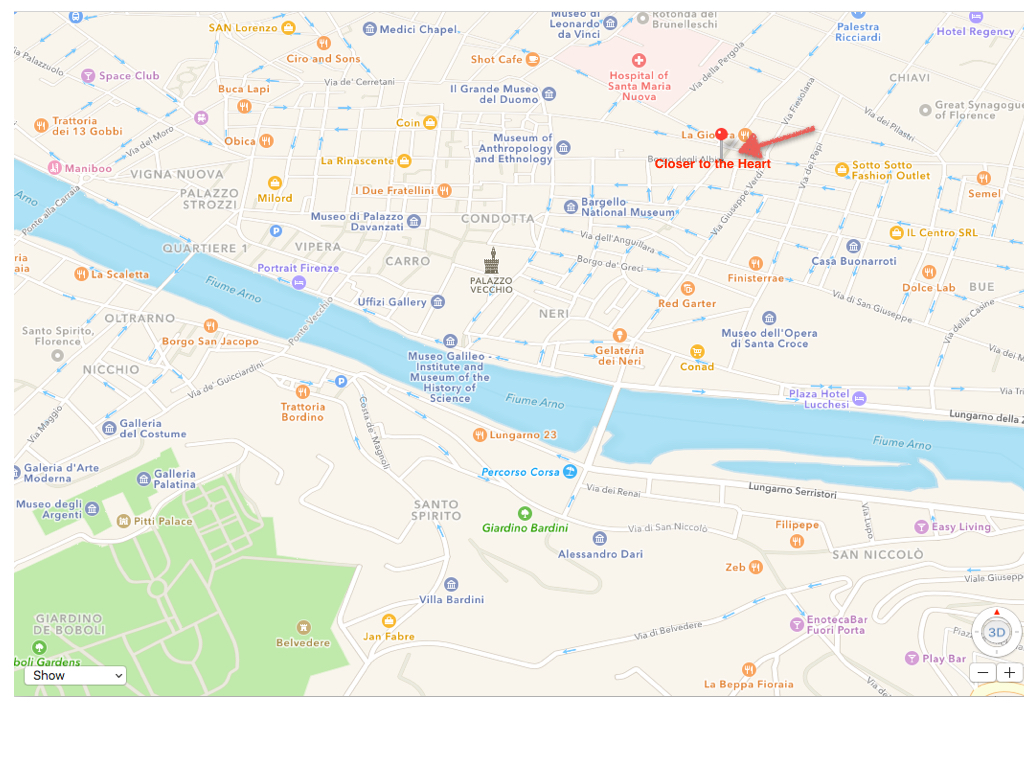

Via Matteo Palmieri, Florence - Italy

From Via Ghibellina to Piazza San Pier Maggiore, in the Santa Croce quarter.

Matteo Palmieri, learned pharmacist, born in Florence in 1406 and there deceased in 1475. “Think what the medici (doctors) have achieved in Florence, if the speziali (pharmacists) have been the purveyors” Giovan Battista Gelli wrote in his “Capricci del Bottaio”.

The Palmieri family, of Germanic origin, had noble roots and had once owned vast amounts of land in the Mugello area.

However, their assets now amounted to very little, and Matteo, once his elder brother died, was forced to take his place to help his father Marco, druggist in the Canto alle Rondini (See Via Martiri del Popolo). Up until then, in Renaissance Florence, Matteo had studied Latin with Sozomeno, Greek with Marsupini and the Holy Scriptures with the Camaldolese monk Ambrogio Traversari. He was also well inclined towards Maths.

He carried out his profession as a pharmacist, taking on also roles in the art world, becoming consul in 1451. In 1434 he was part of the Great Balia, which proclaimed the return of Cosimo de' Medici from exile, and as a friend of Cosimo, took on a great deal of important roles: Captain in Livorno, Pistoia and Volterra, Vicar in Valdinievole. He was the owner of the Palagio alla fonte dei tre visi, near the Mugnone river, where, according to Boccaccio, the young characters in the Decameron met. (See Via Boccaccio).

He was Prior of the Signoria, and became, in 1453, Gonfaloniere di Giustizia (Bearer of Justice). King Alfonso of Aragon, hearing him speak three languages as an ambassador, Latin, Italian and Spanish, was startled to hear he was a pharmacist. He was bestowed with great honours later in life, and at his death, was granted a solemn funeral in the Church of San Pier Maggiore, attended by Lorenzo de' Medici, politicians, philosophers and poets. He was buried in the family chapel, where he himself had placed a painting, perhaps by Botticini and now in the National Gallery in London, depicting Our Lady of the Assumption up in the sky, among a chorus of angels and his wife Niccolosa, who invoked the help of the Queen of the Skies.

The spicery of the Canto alle Rondini (The swallows' song) was located behind the abse of the Church of San Pier Maggiore, and was thus called because the house of the Uccellini Family (Uccellini-Small birds) had its banner there, formed by three silver swallows, flying in the middle of a red shield.

Above the Casa Palmieri, instead, in Via dei Pianellai, now Pietrapiana, the pharmacist's bust was placed. It was modelled by Antonio Gamberelli, known as Rossellino. It is a striking example of realism, and is found at the Bargello Museum, a little worn by having been outdoors for so many centuries.

Matteo Palmieri's fame didn't only derive from his professional and political profession. He was also the author of historical and political works: De temporibus, De captivate Pisarum, Istoria florentina, Vita civile, and most of all, the mediocre allegorical poem, Città di vita, in a style imitating Dante's Divine Comedy. It told the story of the blessed life of souls, and Palmieri, who followed the current Platonic theories on the world, believed they existed before birth. This led to him being accused, after his death, of being an Originarian, and centuries later, was considered to be a pioneer of metempsychosis. One would believe that this was simply an error of judgment committed more by Palmieri the pharmacist than the theologist, which he certainly wasn't; had it not been for the fact that the pharmacist, poet, theologist, registered his written work with notaries, so it be rendered public after his death.

It was however forgotten, until, in 1557, during one of the recurring floods of the river Arno, which inundated the seat of the Proconsolo, brought the poem to light once again.

The street has been recently renamed after this erudite and politically acclaimed pharmacist, because it's in the vicinity of the Canto alle Rondini,

Captions:

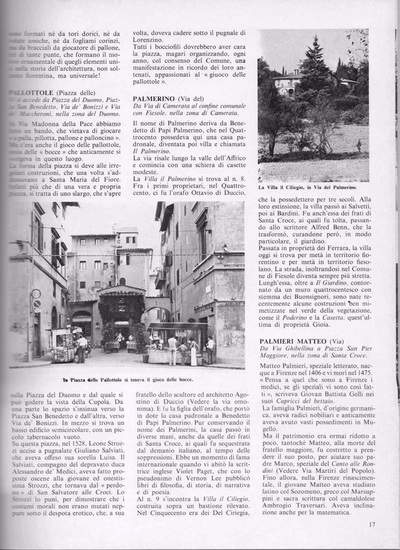

Center PAGE top left image: A pharmacy in the 15th century, with decorated vases)

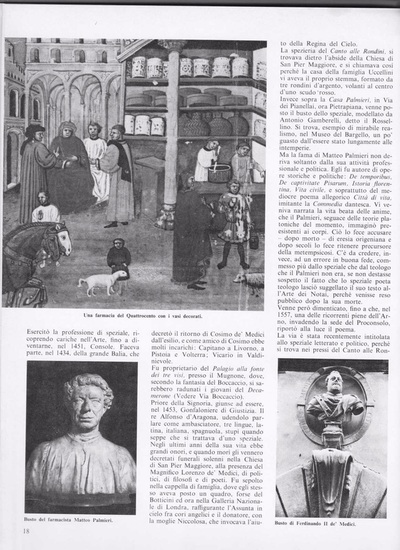

bottom left image: Bust of pharmacist Matteo Palmieri

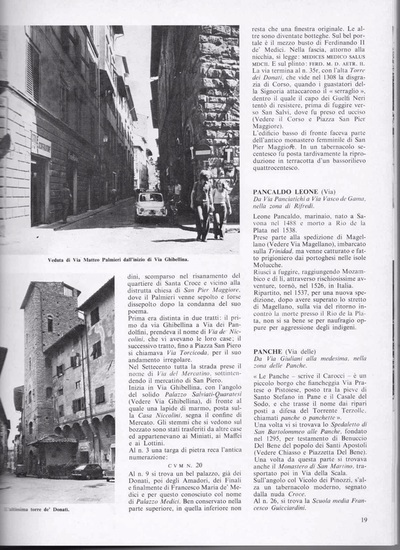

bottom right image: Bust of Ferdinand II de' Medici

which was pulled down during the rebuilding of the Santa Croce district, and close to the destroyed Church of San Pier Maggiore, where Palmieri was buried and perhaps exhumed and moved after his poem being condemned.

It used to be separated in two: the first tract going from Via Ghibellina to Via dei Pandolfini, and carried the name Via de' Niccolini, who had their houses there; and the second tract, running into Piazza San Piero, which was called Via Torcicoda, (curly tail) due to its irregular conformation.

In the 1700s, the entire street bore the name Via del Mercatino, getting its name from the small San Piero street market.

It begins in Via Ghibellina, on the corner of the imposing Palazzo Salviati-Quaratesi (see Via Ghibellina), in front of which, a marble slab, placed above the Casa Niccolini, marks the market's boundary. The coat of arms seen on the rusticated walls were placed there from other houses, and belonged to the Miniati, the Maffei and the Lottini.

At house number 3, a stone plaque bears the ancient numbering:

CVM N.20

At number 9 is a beautiful building, which had initially belonged to the Donati family, then the Amadori, the Finali, and lastly, by Francesco Maria de' Medici, and thus known as Palazzo Medici. Well preserved in its upper level, the lower level now bears only one of it original windows. The others were turned into shops. Above the main door is a half bust of Ferdinand II de' Medici. In the strip that runs along the niche, is written: MEDICES MEDICO SALUS MDCII, and on the plinth: FERD. M. D. AETR II. The street ended at number 35r, with the tall Torre dei Donati, which was the location of the Tragedy of the Corso, when the troops of the Signoria attacked the “brothel” inside which the head of the Black Guelphs tried to resist, before having to then flee to San Salvi, where he was caught and executed. (See the Corso and Piazza San Pier Maggiore).

The low building in front was part of an ancient female monastery of San Pier Maggiore. Inside a 17th century tabernacle there was later placed a copy of a terracotta bas-relief.

Captions:

Page on the right Top image: View of Via Matteo Palmieri at the top of Via Ghibellina.

Lower image: The tall Torre de' Donati.

We would like to thank you Mrs. Dory, Art History Teacher at the University of Florence, for providing us with these precious and interesting informations about the history of "our home".

From Via Ghibellina to Piazza San Pier Maggiore, in the Santa Croce quarter.

Matteo Palmieri, learned pharmacist, born in Florence in 1406 and there deceased in 1475. “Think what the medici (doctors) have achieved in Florence, if the speziali (pharmacists) have been the purveyors” Giovan Battista Gelli wrote in his “Capricci del Bottaio”.

The Palmieri family, of Germanic origin, had noble roots and had once owned vast amounts of land in the Mugello area.

However, their assets now amounted to very little, and Matteo, once his elder brother died, was forced to take his place to help his father Marco, druggist in the Canto alle Rondini (See Via Martiri del Popolo). Up until then, in Renaissance Florence, Matteo had studied Latin with Sozomeno, Greek with Marsupini and the Holy Scriptures with the Camaldolese monk Ambrogio Traversari. He was also well inclined towards Maths.

He carried out his profession as a pharmacist, taking on also roles in the art world, becoming consul in 1451. In 1434 he was part of the Great Balia, which proclaimed the return of Cosimo de' Medici from exile, and as a friend of Cosimo, took on a great deal of important roles: Captain in Livorno, Pistoia and Volterra, Vicar in Valdinievole. He was the owner of the Palagio alla fonte dei tre visi, near the Mugnone river, where, according to Boccaccio, the young characters in the Decameron met. (See Via Boccaccio).

He was Prior of the Signoria, and became, in 1453, Gonfaloniere di Giustizia (Bearer of Justice). King Alfonso of Aragon, hearing him speak three languages as an ambassador, Latin, Italian and Spanish, was startled to hear he was a pharmacist. He was bestowed with great honours later in life, and at his death, was granted a solemn funeral in the Church of San Pier Maggiore, attended by Lorenzo de' Medici, politicians, philosophers and poets. He was buried in the family chapel, where he himself had placed a painting, perhaps by Botticini and now in the National Gallery in London, depicting Our Lady of the Assumption up in the sky, among a chorus of angels and his wife Niccolosa, who invoked the help of the Queen of the Skies.

The spicery of the Canto alle Rondini (The swallows' song) was located behind the abse of the Church of San Pier Maggiore, and was thus called because the house of the Uccellini Family (Uccellini-Small birds) had its banner there, formed by three silver swallows, flying in the middle of a red shield.

Above the Casa Palmieri, instead, in Via dei Pianellai, now Pietrapiana, the pharmacist's bust was placed. It was modelled by Antonio Gamberelli, known as Rossellino. It is a striking example of realism, and is found at the Bargello Museum, a little worn by having been outdoors for so many centuries.

Matteo Palmieri's fame didn't only derive from his professional and political profession. He was also the author of historical and political works: De temporibus, De captivate Pisarum, Istoria florentina, Vita civile, and most of all, the mediocre allegorical poem, Città di vita, in a style imitating Dante's Divine Comedy. It told the story of the blessed life of souls, and Palmieri, who followed the current Platonic theories on the world, believed they existed before birth. This led to him being accused, after his death, of being an Originarian, and centuries later, was considered to be a pioneer of metempsychosis. One would believe that this was simply an error of judgment committed more by Palmieri the pharmacist than the theologist, which he certainly wasn't; had it not been for the fact that the pharmacist, poet, theologist, registered his written work with notaries, so it be rendered public after his death.

It was however forgotten, until, in 1557, during one of the recurring floods of the river Arno, which inundated the seat of the Proconsolo, brought the poem to light once again.

The street has been recently renamed after this erudite and politically acclaimed pharmacist, because it's in the vicinity of the Canto alle Rondini,

Captions:

Center PAGE top left image: A pharmacy in the 15th century, with decorated vases)

bottom left image: Bust of pharmacist Matteo Palmieri

bottom right image: Bust of Ferdinand II de' Medici

which was pulled down during the rebuilding of the Santa Croce district, and close to the destroyed Church of San Pier Maggiore, where Palmieri was buried and perhaps exhumed and moved after his poem being condemned.

It used to be separated in two: the first tract going from Via Ghibellina to Via dei Pandolfini, and carried the name Via de' Niccolini, who had their houses there; and the second tract, running into Piazza San Piero, which was called Via Torcicoda, (curly tail) due to its irregular conformation.

In the 1700s, the entire street bore the name Via del Mercatino, getting its name from the small San Piero street market.

It begins in Via Ghibellina, on the corner of the imposing Palazzo Salviati-Quaratesi (see Via Ghibellina), in front of which, a marble slab, placed above the Casa Niccolini, marks the market's boundary. The coat of arms seen on the rusticated walls were placed there from other houses, and belonged to the Miniati, the Maffei and the Lottini.

At house number 3, a stone plaque bears the ancient numbering:

CVM N.20

At number 9 is a beautiful building, which had initially belonged to the Donati family, then the Amadori, the Finali, and lastly, by Francesco Maria de' Medici, and thus known as Palazzo Medici. Well preserved in its upper level, the lower level now bears only one of it original windows. The others were turned into shops. Above the main door is a half bust of Ferdinand II de' Medici. In the strip that runs along the niche, is written: MEDICES MEDICO SALUS MDCII, and on the plinth: FERD. M. D. AETR II. The street ended at number 35r, with the tall Torre dei Donati, which was the location of the Tragedy of the Corso, when the troops of the Signoria attacked the “brothel” inside which the head of the Black Guelphs tried to resist, before having to then flee to San Salvi, where he was caught and executed. (See the Corso and Piazza San Pier Maggiore).

The low building in front was part of an ancient female monastery of San Pier Maggiore. Inside a 17th century tabernacle there was later placed a copy of a terracotta bas-relief.

Captions:

Page on the right Top image: View of Via Matteo Palmieri at the top of Via Ghibellina.

Lower image: The tall Torre de' Donati.

We would like to thank you Mrs. Dory, Art History Teacher at the University of Florence, for providing us with these precious and interesting informations about the history of "our home".